Russia Became a Communist Hellhole Because of This Man

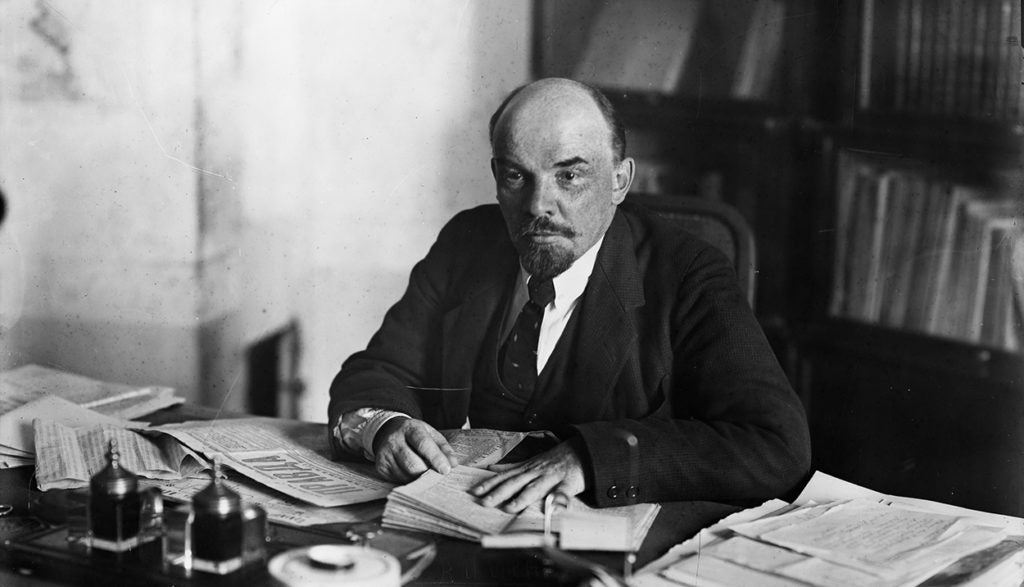

To understand communism, it’s important to look at the man who was the first to institute a government dedicated to Karl Marx’s ideals: Vladimir Lenin.

When I was in college, I recall a conversation with several classmates who joked about throwing a get-together and naming it “The Communist Party.” They mocked the idea that anyone would fear this supposedly well-meaning ideology.

I wonder if they would have been laughing if they were in the presence of gulag survivors.

This Nov. 7 marks the 102nd anniversary of Lenin’s rise to power in Russia, and Nov. 9 will mark the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the symbol of tyranny built by the regime he forged.

Victor Sebestyen’s 2017 biography on Lenin—the first major biography of the Soviet leader to hit Western bookshelves in two decades—documents his many crimes against humanity.

Lenin’s streak of cruelty began long before he came to power. By his early 20s, his zealous dedication to Marxism led him to believe that anything justified revolution.

Cruelty Without a Conscience

When a famine broke out in the Volga region in 1891—one that would kill 400,000 people—Lenin welcomed the event, hoping that it would topple the Czarist regime. His sisters, dedicated revolutionaries themselves, assisted with relief efforts for the starving and were shocked by his callous refusal to help.

Later, in 1905, when Czarist forces killed hundreds of striking workers and 86 children in Moscow, Lenin refused to mourn for the dead and, instead, hoped the event would further enflame class antagonisms. In his eyes, human lives were expendable in the pursuit of the workers’ paradise.

Lenin would spend a career castigating and eliminating competitors who he believed had deviated from what he considered “true” Marxism. As Sebestyen notes, though, “The first major ‘deviationist’ was Lenin, who frequently turned Marxism on its head when it didn’t suit his tactical purposes.”

In other words, Lenin was a hypocrite who would purge others for revising Marx, but reserved that right for himself.

Marx had asserted that broad, impersonal (not individual), and material forces controlled the course of history. He also didn’t envision the revolution of the urban proletariat happening in the largely agrarian Russian Empire.

No matter—it could happen in Russia, because Lenin said so and would make it happen (which he did). So much for broad, impersonal forces.

Thus, Lenin ushered in the longtime communist practice of manipulating ideology to obtain whatever was desired.

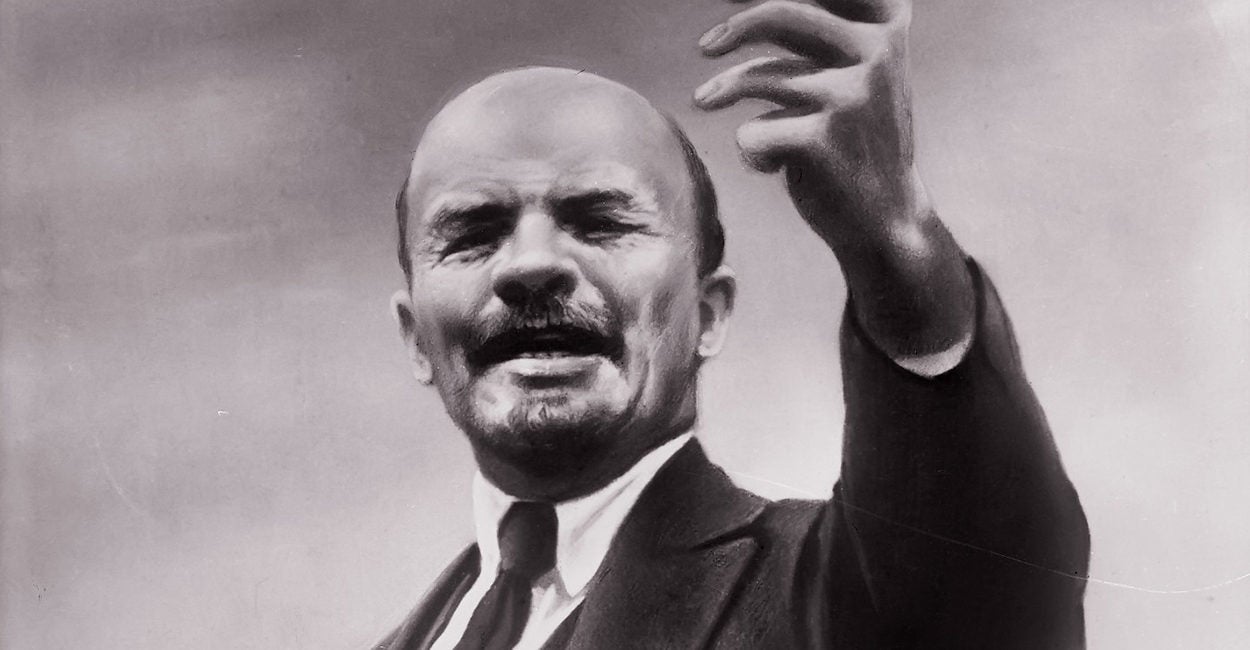

Stoking the Flames of Revolution

Before taking power, Lenin spent much of his life under house arrest in Siberia or in exile abroad, living in the United Kingdom, France, and Switzerland—countries that one day would face an existential threat from the regime he would create.

He established himself as a major leader in the underground communist movement. Reading Sebestyen’s account makes it seem that Lenin was the head of some sort of secretive startup enterprise.

Lenin was constantly raising funds and generating support. He wrote and printed subversive literature, distributing it through underground networks.

At times, it looked as though Lenin’s venture was on the brink of collapse, and no one else seemed to believe he would amount to anything—except, it seemed, Lenin himself.

He survived, in part, by living off his mother’s funds. History seems to indicate that dependency combined with radicalism is rarely a good thing. Osama bin Laden, too, was an extremist who lived off his family’s wealth while financing his Islamist activities.

A series of tragic incidents led this foundering communist to eventually take control over the world’s largest country by landmass. Germany invaded Russia, the Czar showed disastrous leadership, and Berlin ultimately sent the exiled Lenin back to Russia to destabilize it and remove it from the war.

It also helped Lenin’s cause that he had the perfect slogan for a suffering populace: “peace, land, and bread.”

While in exile, Lenin railed against the imperial government for its oppressive ways—for instance, its censorship of the opposition and dismissal of parliament. Of course, once in power, Lenin repeated these policies and usually exceeded their cruelty, imprisoning and confiscating the property of his opponents.

When it came to hypocrisy, the sky was the limit for Lenin. Sebestyen recounts one instance in which Lenin was indignant after his bicycle was stolen. The irony was surely lost on him.

A Regime of Torture and Murder

Lenin appointed the homicidal Felix Dzerzhinsky to head up the Cheka (the secret police) with orders “to fight a merciless war against all enemies of the revolution. … We are not in need of justice. It is war now.”

In less than a year, hundreds, if not thousands, were executed—including Nicholas II and his family. He would be the last emperor of Russia.

In a move that prefigured Mao Zedong’s later Cultural Revolution in China, Lenin incited class warfare across the Soviet Union.

He marked wealthy peasants, or kulaks, as enemies of the revolution and encouraged violence against them. He imposed fixed grain prices at low rates, straining peasants who already were living on the margins, seized their grain, and left them to starve.

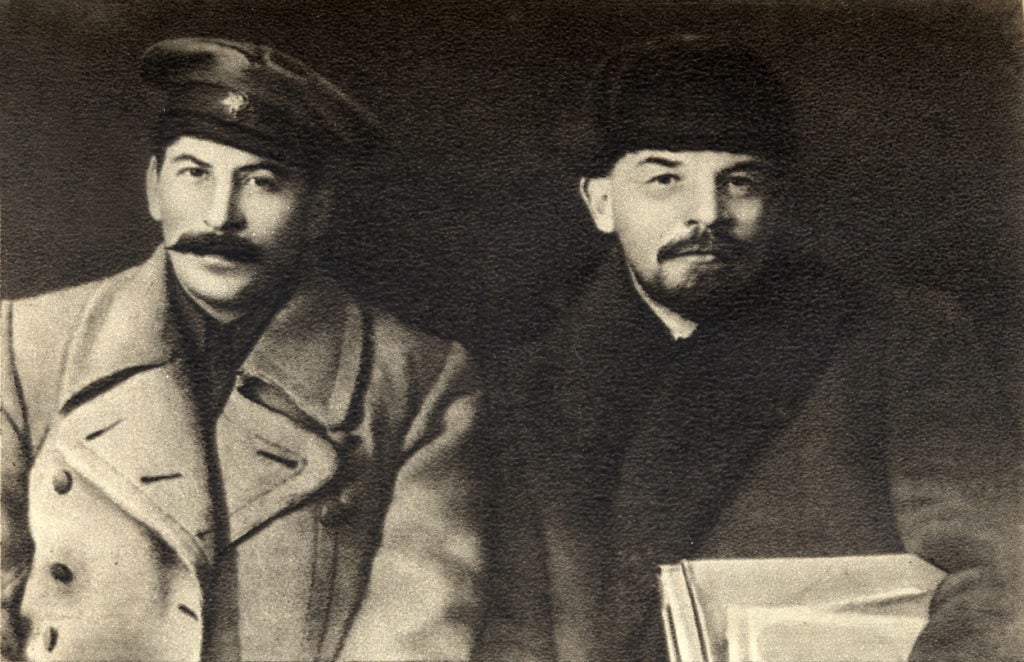

When the peasants began resisting, Lenin ordered government officials to torture them or apply poison gas. He specifically ordered his henchman, Josef Stalin, to be ruthless in taking grain from Tsaritsyn.

When those tactics contributed to yet another famine in the Volga area, he refused to provide relief and did so only after being forced by his advisers. American official Herbert Hoover, who was running humanitarian efforts in Europe during World War I, offered his services to the Soviet government.

For those who scoff at the idea that communism was an inherently expansionist regime, Lenin created Communist International, or “Comintern,” to spread the revolution around the world. At times, more funds were spent to spread propaganda abroad (including in the United States) than on famine relief.

The End of One Man, the Beginning of a Disaster

An assassination attempt and a series of strokes weakened Lenin and, by 1923, he was dying. By then, he came to believe Stalin was too heavy-handed to be his successor (he would know), even saying as much in his famed Last Testament (which was later suppressed).

Lenin died in January 1924, having failed to dislodge Stalin from power. As bad as Lenin was, somehow, even greater suffering awaited the Russian people.

After a lifetime of serving the Soviet government at the highest levels, Vyacheslav Molotov reflected on the two men, saying that both were “hard men … harsh and stern.” He added, “Without a doubt, Lenin was harsher.”

The regime that Lenin founded would eventually impose totalitarian dictatorships over its Eastern European neighbors and threaten the existence of the West, but ultimately would collapse in 1991 under the weight of its own contradictions.

The Soviet Union may no longer exist today, but the Communist Party in China remains firmly entrenched. Few regimes can match the levels of totalitarianism practiced under Lenin, Stalin, and Mao, yet Beijing continues to disregard human life in its pursuit of the promised Marxist utopia.

The United States has never been a perfect country, but we can be thankful that it avoided the autocratic and ideological extremes of the 20th century.

The far left is always looking to publicize injustices here at home. By that standard, the story of Lenin ought to receive more attention than any other.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario